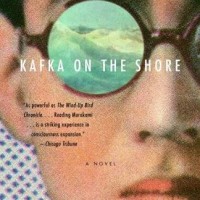

Book Review – Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

On the surface, a surreal and fantastical story about the intertwining narratives of a teenage boy running away from home to escape an Oedipal prophecy, and the journey of an elderly mildly retarded man who can talk to cats, doesn’t seem exactly like the kind of material I normally post about on this blog. But Kafka On The Shore really struck me with some fantastic insights about the mind and the nature of consciousness and I felt compelled to write about it. So much so that I wasn’t sure whether it’d be best to write this as a review of the book, or a post about consciousness; hopefully at the end it will be both. I’m going to do my best not to spoil specific events in the story, but since I WILL be talking about ideas at the heart of this book, you are officially SPOILER warned.

There was one fundamental insight and idea in this story that all the important aspects of the book stem from. This is the idea that “everything is metaphor”. Now, on this surface this might simply sound like it means that the events in the book and story being told are really a metaphor for something bigger that the author is trying to tell, and this certainly the case. But on a deeper level the author, Haruki Murakami, is making a really profound statement about the nature of human existence and consciousness….EVERYTHING is metaphor. Let me explain. Metaphor is normally defined as understanding one thing in terms of another. And as we go through our lives talking with and interacting with people, we think of most of our communications as literal communication, with metaphor being used only at certain times in story telling or when illustrating a point, or what have you. But if we take the perspective of cognitive science, and what we know about the nature of mental phenomena and communication, we’re forced to the conclusion that everything IS metaphor.

Our basic mode of communication, language, is already a way of understanding something in terms of something else. Using language is an interpretive act. And it’s an interpretive act in two ways. One is in the sense that one person’s mental states are interpreted by another person, by means of the words that are said from one person to another. Words are symbols, which I must use to interpret the contents of your mind. We forget to that while communication presents to us the façade of direct access, this is really an illusion, or at least a not quite solid assumption. I have no real access to what’s going on in your head, I only have an interpretation based on the words that come out of your mouth, themselves sometimes second rate approximations of a much more complex storm of mental activity. A slightly finer point is that we sometimes forget that words themselves are meaningless. Words are just mechanical waves moving through the air. They are sounds, like any other sounds. And when they interact with our auditory system, they are turned in electrical impulses in the brain. And somewhere down the line we (or our brains) interpret these impulses as having some sort of special meaning that other sounds don’t have. We are interpreting words in terms neuronal firing, metaphor at its best if you ask me. There is a great character in the story that brings these ideas home. Being somewhat slow and lacking in intelligence, the character doesn’t understand metaphors. But he also doesn’t understand many common things we forget are really metaphors, like money. Money to him is not “real”, it is this hard to grasp abstract idea, as are all sorts of other common phrases and things in our world. By embodying the antithesis to “everything is metaphor”, this character reminds us of that simple truth which we take for granted.

This idea of metaphor doesn’t stop at language. Our entire conscious perceptual experience of the world can be looked at as a metaphor in the same way. I’ve written about this before, but we look out at the world and we think we’re really seeing the world, directly perceiving what is around us. But we now know that this isn’t the case, that our conscious experiences (and thus our perceptual experiences) are a constructed process. You are constantly being bombarded by various “signals” from the outside world. Mechanical waves in air, electromagnetic waves, free floating molecules, and your brain interprets these interactions, what we call signals, by first converting them into electrical impulses and somehow along the way making sense (no pun intended) of them. We interpret the outside world via our senses, we never really experience that outside world directly.

This fact has all sorts of implications for the nature of consciousness, the self, the content of mental states and the objects we interact with, which Murakami delves into in some pretty creative ways. But as a way of explaining what I mean here, let’s think about the nature of objects out there in the world. You don’t have direct access to any objects. You experience objects through the interactions they have with your sensory systems. So while an object may have its own independent existence outside of you, your experience is not the same as that object. This table here in front of me…it looks real. It feels real. But all of this a constructive process my brain is doing. Think about the myriad of hallucinations and perceptual illusions we are susceptible to, as well as altered states of consciousness that come about through drugs or brain damage. What we experience is not necessarily how things are…out there. It is an interpretation based on our various sensory signals and interactions. Objects can simply be viewed as features of our own consciousness. Objects, as we experience them, are the content of our mental states, nothing more.

But we can’t stop there; people must be the same in this way. I’m a real conscious being, and you’re a separate real conscious being. I’ll grant that. But if all I really have access to is my own conscious experience, then other people, like any other objects, are just an aspect of my conscious experience. You are just an object out there in the world, and like any sensory experience, my experience of you is just a content of my mental state. Who you are to me is not the same as who you are to you (at least there is no necessary relationship between the two), rather, who you are to me is simply my interpretation of you, an aspect of my consciousness. (I should note though, one of the goals, or at least one of the most wonderful things about language, is that it allows us to bridge the gap between reality and our mental concepts of other people in amazing ways, something Murakami doesn’t really focus on.)

These are all important elements of Kafka on the Shore (in a metaphorical way), but what stems from these ideas next, is what ends up being most important to the story Murakami tells. If objects and people are just features of our conscious experience, then what they mean to us is a matter of personal interpretation, it is a matter of choice. We have to accept that to a certain degree we all “use” the people in our lives for our own purposes, no matter how altruistic those purposes are. People are objects (in the strict mental content sense of the word) that provide very responsive interactions for our conscious experience, but because who these people are, is an interpretation, it’s almost as if who they are is something we impose on them. And we interact with them based on this interpretation/imposition.

So who you are to me is a choice I make, not you. And how I choose to interact with you is based on how I believe my conscious experience will progress based on that interpretation. If I do something because I believe it will make you happy, it is because making you happy is somehow in my self interest, something I desire, and why I think it will make you happy, and who I think you are, is all part of my consciousness, with no necessary relation to reality (i.e. – it might not actually make you happy, because I could be wrong about you). If I write a letter to you bearing all to get something I need off my chest, it is the process of writing the letter that was important, it was getting it off my chest that was important. How you respond to it and whether you even read it, is not something I can control, but I used you as a vessel to go through a certain process (this is an example from the book). And so similarly, throughout this book you see characters choosing to view people in certain ways, choosing to interact with people in certain ways, imposing their own metaphors on the world that they are interacting with. It is filled with people doing things, kind acts, for other people, not *for* the other people, but for themselves, for their own reasons. Objects of our consciousness are like vessels for a process of self growth (ideally). And it is only when the main character of the story realizes the truth behind choice, consciousness, and metaphor that he is able to complete the journey he is on.

In the end this book is about a lot of things, but you take away some strong ideas about choice and the nature of the self, and how this all plays apart in personal growth and development. It’s a very interesting exploration of this balance between self reliance and human relationships, between love and friendship and the self, given that everything must be interpreted by me in one way or another. Everything, every relationship we have, every interaction we have is all part of this feedback loop of this ongoing temporal process that we call consciousness, and it is in understanding the truth of this that allows us to grow and develop. (This last bit is what I’m interpreting Murakami to be saying, but it’s something I happen to agree with myself) But I’d like to add my own addendum of something that Murakami doesn’t focus on (he brings this up briefly when discussing Hegel and content and relations), which is that interpretations aside, lets not forget that other people are real people with their own thoughts and feelings and desires. And in the same way that you are an aspect of my consciousness, I am an aspect of your consciousness. I am your content. We all exist and interact in this tangled web of cause and effect. How I act towards my friends and loved ones (or anyone) aren’t simply features of my consciousness that help me grow, they are real interactions that themselves affect the lives of others. A process of self development, of interaction, that doesn’t respect this fact, will I think forever limit the capacity of the individual to truly grow in the way Murakami describes.

One Response

10:17 am

Kafka on the Shore – A sensational journey into the mesmerizing realm of forbidden love and fantastic concepts which is both haunting and enlightening. Your Comments