The Neuroscience of Philosophical Hypotheticals

Note – This is part 3 of 6 of my ongoing series on morality. Links to previous entries are at the bottom.

Anyone who has even a basic familiarity with philosophy, or has stayed up late arguing with friends after a few drinks, has probably at one time or another been posed with some sort of hypothetical situation. Hypotheticals are both difficult to answer and interesting to contemplate precisely because we are posed with a situation we have never been in, and might never be in. Many argue that hypotheticals are useless precisely for this reason. Neuroscientists disagree. Because we are forced to think about things in ways we are normally unused to, by studying the brain during this process and correlating the observed brain function with the eventual answer to the hypothetical, we are able to learn all sorts of interesting things about the constituents of our behavior and decision making. In keeping with our theme of morality, today I’m going to take a look at a few famous moral philosophical hypotheticals, and what we have learned about morality by studying them scientifically.

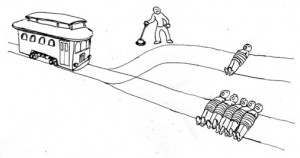

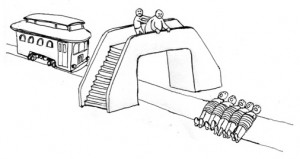

In a series of studies, Joshua Greene studied the human brain while participants made various moral decisions. A famous philosophical thought experiment called The Trolley Problem was the first one addressed. In the first case, a runaway trolley is heading down a track, headed for five people who will be killed if it continues down its present course. The only way to save these five people is to flip a switch and divert the trolley onto an alternate track, where it will kill one person who happens to be on this alternate track. To save five people you must kill the one person. Most people given this question choose to divert the train, and kill the one person, and cite this action as the moral decision to make. An alternate version of this dilemma, sometimes called The Footbridge Problem, has the same runaway trolley, but this time there is no alternate track to divert it to. You are standing atop a footbridge next to an extremely large man. You can push this man off the bridge, and his body will stop the trolley from killing the five men, but in the process you will kill this man. Most people say they would not push the man,

In a series of studies, Joshua Greene studied the human brain while participants made various moral decisions. A famous philosophical thought experiment called The Trolley Problem was the first one addressed. In the first case, a runaway trolley is heading down a track, headed for five people who will be killed if it continues down its present course. The only way to save these five people is to flip a switch and divert the trolley onto an alternate track, where it will kill one person who happens to be on this alternate track. To save five people you must kill the one person. Most people given this question choose to divert the train, and kill the one person, and cite this action as the moral decision to make. An alternate version of this dilemma, sometimes called The Footbridge Problem, has the same runaway trolley, but this time there is no alternate track to divert it to. You are standing atop a footbridge next to an extremely large man. You can push this man off the bridge, and his body will stop the trolley from killing the five men, but in the process you will kill this man. Most people say they would not push the man,  and cite the act of pushing him as an immoral action. Thus we have two different actions, both of which lead to the same result, and yet which most people view in completely opposing ways. What I want to know is not whether neuroscience can tell us which action is right or wrong, but why we make these two different decisions when posed with this dilemma. And why most people who answer it are so sure one way or the other.

and cite the act of pushing him as an immoral action. Thus we have two different actions, both of which lead to the same result, and yet which most people view in completely opposing ways. What I want to know is not whether neuroscience can tell us which action is right or wrong, but why we make these two different decisions when posed with this dilemma. And why most people who answer it are so sure one way or the other.

What Greene found was that when making the decision to divert the trolley there is activation in brain regions associated with abstract reasoning and cognitive control. And when making the decision to not push the man off the bridge there is more activation in areas associated with emotion and cognition. These results showed us that there are systematic variations in the engagement of our emotional centers during moral judgment, and that these variations manifest themselves as observed correlations between this activation, and the moral judgment made.

Greene wanted to dig further though, and later ran a follow up experiment. Whereas in the first case he had two different types of responses to two different types of situations, this time he wanted to study two different types of responses to the same situation. One hypothetical that worked well for this was the Crying Baby Dilemma. In this thought experiment enemy soldiers have invaded your village, with orders to kill all civilians they find. You and a group of other villagers have found refuge in a cellar of a large house. You have a baby who begins to cry loudly, so you cover its mouth. If you remove your hand from your baby’s mouth, the enemy soldiers will hear it, and will kill you, your baby, and all the villagers. But if you keep your hand covering your baby’s mouth, the baby will suffocate and die. Is it appropriate for you to smother your baby in order to save yourself and your fellow villagers?

This is understandably an extremely difficult dilemma to resolve for most people, with no clear consensus regarding what is the appropriate action to take. You might even argue that there IS no right answer to the question. But how we answer it, and what is going on in the brain while we do can tell us a lot. Greene found that during these difficult moral decisions there was increased activation in both the areas discussed above (the reasoning area and the emotional area), as well as another area involved in mediating cognitive conflicts. Further, increased activation of the areas responsible for abstract reasoning and cognitive control (as related to the emotional area), corresponded with more utilitarian judgments made in regards to these difficult dilemmas (i.e. – it’s appropriate to smother the crying baby). Basically, what they found was that the decision to let the baby cry was correlated with activation in the emotional center, while the decision to smother the baby was correlated with activation in the abstract reasoning area. Whichever area wins out, is what you will do.

This research has not only localized different aspects of moral decisions to particular brain regions, but also correlated these same moral decisions with their relative activation levels. Correlation is not causation though, and so it’s worth mentioning another study that sought to answer whether emotions play a causal role in moral judgments. In a study focused on patients with damage to their emotional centers, researchers studied whether this damage would affect an individual’s moral judgment. These patients have intact capacities for general intelligence, logical reasoning, and knowledge of social and moral norms, but where they suffer is in exhibiting standard emotional response and regulation, often exhibiting reduced levels of compassion, shame, and guilt. The study results showed that patients with damage to this area produce an abnormally high level of utilitarian judgments when presented with various moral dilemmas that normally pit emotionally aversive behaviors versus considerations of aggregate welfare for the greatest number of individuals. They made logical and rational decisions, but without their emotional center pulling them in a particular direction, they tended to make moral judgments that many of us would would find troubling.

So what does all this mean? The result of this research seems to imply that our emotional system, an evolved brain system, has a large causal role in creating our moral intuitions, and that deficiencies in this system lead to significant differences in our moral judgments. It’s also important to point out that while providing great insight into the biological and neuronal factors involved in the decision making process, none of this research tells us anything about which judgments are right or wrong. Though it does shed some light on the origins of our two of most prevalent ethical theories. Consquentialism (the theory that the rightness or wrongness of an act lies within the consequences of any particular action) and Deontology (which argues that it is not the outcome, but the character of the action itself which determines moral rightness) can now be viewed as a struggle between two brain systems, the evolutionarily older emotional (deontological) system, and the newer cognitive (consequentialist) system (this mapping of one to the other is probably useful more as a narrative, and should not be taken *too* seriously). Though, let’s not jump to any hasty conclusions about the distinction between emotion and rationality. Next time we’ll talk about whether the dividing line between these two areas of consciousness are really able to be divorced from each other, and whether they should be. Should moral decisions be made on a completely rational basis? Or is emotion integral to moral reasoning? In the case of people with damage to their emotional centers, it’s obvious that their consciousness and interaction with the world is altered for the worse. And yet, we also know that emotions often times lead us astray and are based on bias and fear as much as anything else. How are we to think about this apparent divide?

- Science and Morality

- Moral Intuitions vs. Moral Standards

- Philosophical Hypotheticals

- Emotion and Rationality

- Theory of Mind and Moral Judgments

- Morality Wrap-up

7 Responses

4:36 am

[…] A second version is where you stand on a bridge with a fat man. The only way to stop the trolling killing five is to push the fat man in front of the trolley. Do you do so? Some people say no to both and many say yes to switching but no to pushing, referring to errors of omission and commission. You can read about the moral psychology here. […]

9:48 am

How does incorporate being amoral and absurdist and yet take decisions and analyse them,woukd be the same as taking a rational decision devoid of emotions

10:16 am

Hi Prakash, I’m not sure I understand your question. Are you asking how to act when presented with the above situation if you are amoral?

I imagine that in that case you would choose the action that was in line with whatever decision making process you normally engage with the world with. It might not be a moral question for you, but it’s still a situation that requires a decision (understanding that refraining from action is a decision in itself).

9:50 am

How does one incorporate being amoral and absurdist and yet analyse the above dilemma?

6:51 am

Would an amoral decision be different if it were in anonymity, by that i mean would i choose differently in situations where my action would be critiqued at the altar of society(assuming the moral considerations for a amoral person wouldn’t matter personally)

10:06 am

I’m still not sure how to answer your question Prakash. The above post covers specific empirical research that’s been done, but no such research has been done on amoralists (assuming they exist), so I can’t tell you anything about the amoralist’s brain when making that decision. Anything I say about your question would be speculation. But if that’s what you’re looking for, I would answer your question the same way I did above. The amoralist would engage in whatever decision making process they normally engage in. That decision making process may or may not change based on whether the amoralist can act or decide in anonymity, and that difference will likely be some fact about the psychological makeup of the amoralist.

The amoralist might just choose the path of least resistance and make the non-decision, letting events transpire without his or her actions. Or they may decide to act in a way that helps them personally. But I obviously can’t say with certainty.

Is that what you are getting at?

9:08 am

[…] a runaway trolly car. People’s answers differ, but one question is why they differ. The Cognitive Philosophy blog reviews some neuroscience research to help us find the answer: So what does all this mean? […]